Then my teeth were uncomfortabl(ly tight)e in their retainers so those got slipped out, too.

|

| the following quotations are from here (what the...there are youtube renditions of this) |

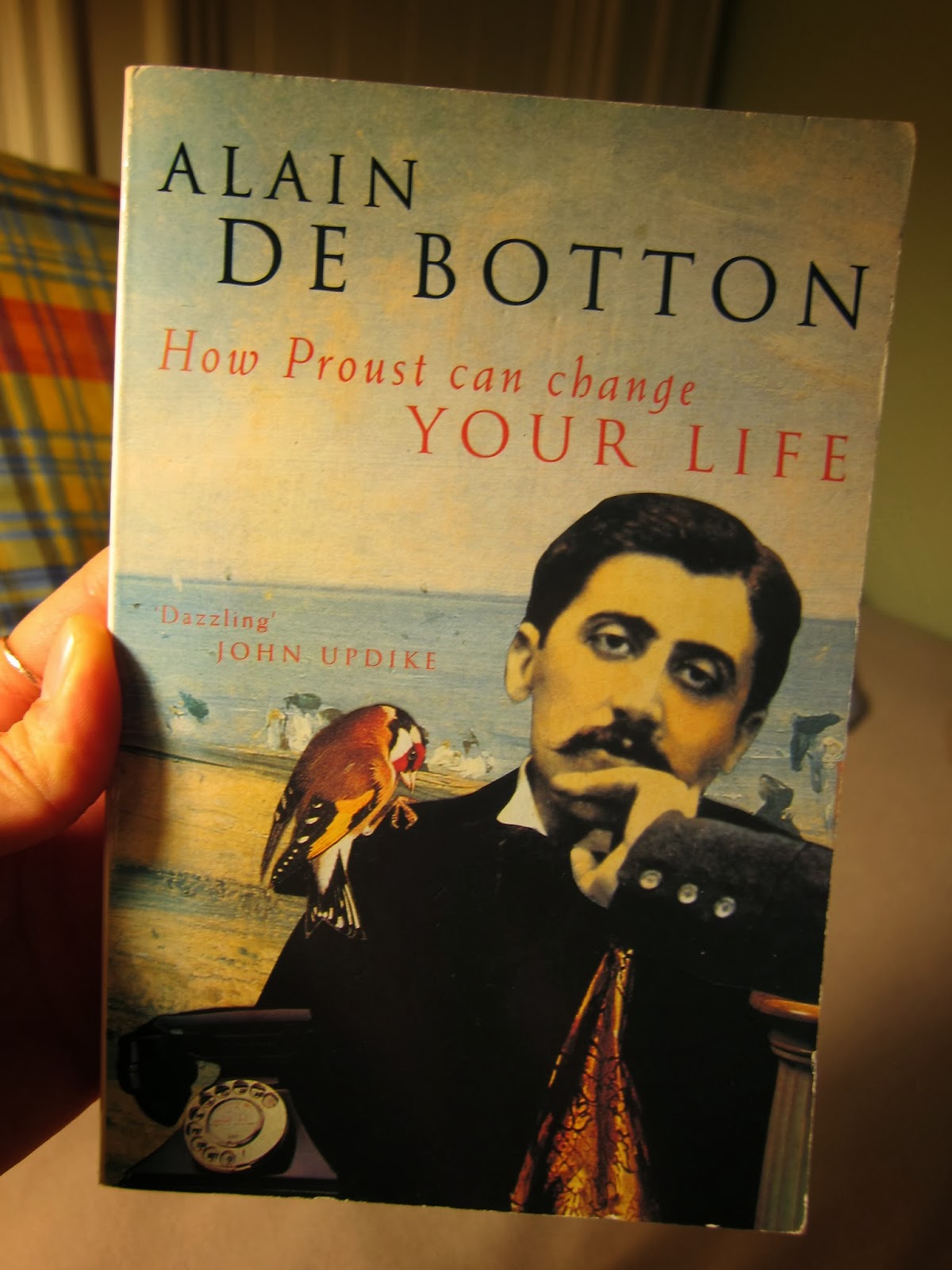

How to Put Books Down:

"...we should be reading for a particular reason: not to pass the time, not out of detached curiosity, but out of a dispassionate wish to find out what Ruskin felt, but because, to repeat with italics, "there is no better way of coming to be aware of what one feels oneself than by trying to recreate in oneself what a master has felt." We should read other people's books in order to learn what we feel; it is our own thoughts we should be developing even if it is another writer's thoughts that help us do so. A fulfilled academic life would therefore require us to judge that the writers we were studying articulated in their books a sufficient range of our own concerns, and that in the act of understanding them through translation or commentary, we would simultaneously be understanding and developing the spiritually significant parts of ourselves.

And therein lay Proust's problem, because in his view, books could not make us aware of enough of the things we felt. They might open our eyes, sensitize us, enhance our powers of perception, but at a certain point they would stop, not by coincidence, not occasionally, not out of bad luck, but inevitably, by definition, for the stark and simple reason that the author wasn't us. There would come a moment with every book when we would feel that something was incongruous, misunderstood, or constraining, and it would give us a responsibility to leave our guide behind and continue our thoughts alone...

It is one of the great and wonderful characteristics of good books (which allow us to see the role at once essential yet limited that reading may play in our spiritual lives) that for the author they may be called "Conclusions" but for the reader "Incitements." We feel very strongly that our own wisdom begins where that of the author leaves off, and we would like him to provide us with answers when all he is able o do is provide us with desires... That is the value of reading, and also its inadequacy. To make it into a discipline is to give too large a role to what is only an incitement. Reading is on the threshold of the spiritual life; it can introduce us to it: it does not constitute it.

It obliges us to read with care, to welcome the insights books give us, but not to subjugate our independence or smother the nuances of our own love life in the process.

Otherwise, we might suffer a range of symptoms that Proust identified in the overreverent, overreliant reader:

.........

Symptom No. 2: That we are unable to write after reading a good book:

Reading Proust nearly silenced Virginia Woolf... "Proust so titillates my own desire for expression that I can hardly set out the sentence. Oh if I could write like that! I cry. And at the moment such is the astonishing vibration and saturation that he procures -- there's something sexual in it -- that I feel I can write like that, and seize my pen and then I can't write like that."

"I detest my own volubility. Why be always spouting words?"

"This is the worst time of all. It makes me suicidal. Nothing seems left to do. All seems insipid and worthless."

"[In Search of Lost Time] which is of course so magnificent that I can't write myself within its arc. For years I've put off finishing it; but now, thinking I may die one of these years, I've returned, and let my own scribble do what it likes. Lord what a hopeless bad book mine will be!"

The tone suggests that Woolf had at last made her peace with Proust. He could have his terrain, she had hers to scribble in. The path from depression and self-loathing to cheerful defiance suggested a gradual recognition that one person's achievements did not have to invalidate another's, that there would always be something left to do even if it momentarily appeared otherwise. Proust might have expressed many things well, but independent thought and the history of the novel had not come to a half with him. His book did not have to be followed by silence; there was still space for the scribbling of others, for Mrs. Dalloway, The Common Reader, A Room of One's Own, and in particular, there was space for what these books symbolized in this context -- perceptions of one's own."

--------------------------------the application:------------------------------

These are layers and layers of genius to grapple with, learn from, and irreverently throw aside after having ingested their healthy juices. As healthy and addictively refreshing as regular bowel movements, a happy colon with a diet full of fiber.

I feel like I am learning how to read from this book. The best kinds of teachers are the ones you can leave behind, aren't they? No matter how good their handwriting, no matter how ingenious their analysis of To the Lighthouse, no matter how inferior you feel in their presence -- actually, the best, the most effective, the most truly inspirational of all teacherly beings are the ones who allow you to stand on their shoulders and look into worlds beyond their own scope. Teachers with teachings that are great enough to cause those heart tremors, but humble enough to allow for the possibility of greater, fiercer vibrations.

Those who equip us with the real tools, of believing in the distinct realizability of our loftiest dreams. In made-up words and over-hyphenization, allll included.

|

| "Lord what a helpless bad book mine will be!" |

There

are unbreathed, disquieted rumblings on the insides of my insides. I can't wait to read A la recherche de temps perdu. I can't wait to finish it and to put it down and then to poop out my own poop (...sorry; stop thinking about it...now!). But for now, it's legs-under-the-covers and retainers, back on: getting prepared for the good work of tomorrow and tomorrow's tomorrow's tomorrows.

No comments:

Post a Comment